Le Kef, Tunisia: On the first anniversary of the Tunisian revolution, international attention largely focused on Avenue Bourguiba in downtown Tunis and on Sidi Bouzid, where the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi on 17 December 2010 is said to have ignited the Arab Spring. But before the revolution ever reached Tunis, it unfolded in smaller towns throughout the country—spreading from Sidi Bouzid to Bou Zayen, Kassrine, Thala, Ghafsa, Le Kef, and Jendouba—well before the first large scale protest was held in the capital on 8 January 2011.

Kasserine and Thala were the first towns to suffer from violent police crackdowns that fueled subsequent protest movements. In solidarity with protesters in Sidi Bouzid, about twenty residents of Thala organized a small protest on 7 January 2011, only to be confronted by three hundreed police officers. In Kasserine, the police shot thirty-five mourners at a funeral of residents killed in clashes just days before. Over fifty protesters were killed in the area, and the Kasserine-Thala Martyrs’ Trial continues to this day, incidentally in the court of Le Kef.

Protesters in Le Kef likewise suffered police-led violence in the weeks before the January 14th Revolution. A Facebook page on 8 January 2011 drew attention to the “carnage in Kef”. Like the towns close to Sidi Bouzid, such as Gafsa, Thala, and Kasserine, Le Kef is a fitting site from which to examine the one-year anniversary of the Tunisian revolution, as it is in such economically depressed and all-but-forgotten areas outside of Tunis where the legacy of the revolution is still being played out.

View from the Margins

Governorate of Le Kef is a very poor municipality with a population of 45,000 and a long history of political dissent. In the 1950s, the mountain-top town served as a military base of the Front de Libération Nationale during the Algerian War of Independence. Situated west of Tunis and twenty-five miles from the Tunisian-Algerian border, it is notable for its fortresses and historic sites relevant to each of the Abrahamic religions. The Ghriba synagogue, the mausoleum of Sidi Bou Makhlouf, Roman ruins, and a basilica draw a trickle of tourists, and the restored casbah offers astounding views of the countryside.

Yet, Le Kef seems to have been consistently overlooked in the twentieth century, by French colonizers, by Habib Bourguiba, and by Zine Abedine Ben Ali. Under the latter’s rule, many men from the town were forced to leave to the coastal zones or to larger cities to find work, though most were unsuccessful and returned empty-handed. Although a majority of the area’s youth hold secondary school diplomas, it is not uncommon to remain unemployed until the age of forty, despite their qualifications. The economic conditions in Le Kef are thus not that different from Sidi Bouzid, Kasserine, Thala, Redeyef, Metlaoui, and Gafsa. And, similar to other towns on the periphery of Tunisia, dissent tends to be organized primarily around economic grievances. Most recently, on 9 December 2011, the border crossing west of Le Kef to Algeria was reopened after being blocked for three days by protests of unemployed youth.

Le Kef thus represents an on-going site of dissent familiar to other neglected locations outside of Tunis, and its residents have grown frustrated with post-revolutionary elite politics in the capital.

[Burnt car from the jasmine revolution.]

On 17 December 2011—the one-year anniversary of Bouazizi’s death—a commemorative statue of Bouazizi’s fruit cart was unveiled in Sidi Bouzid. A few weeks later, on 8 January 2012, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki, Interim Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali, and Constituent Assembly President Mustafa Ben Jaafar travelled to Kasserine to participate in the International Martyrs Festival, held there from 6 January to 10 January 2012. The government officials received a mixed welcome from the town’s residents, some of whom greeted the delegation with excitement while many others participated in protests and sit-ins.

[Downtown Le Kef with fortress in background.]

The contentious reaction to the visit was rooted in a number of recent events. On 22 November 2011, during the first session of the newly elected Constituent Assembly, the interim government ceremoniously read the names of martyrs who were killed by state forces in the weeks leading up to the January 14 Revolution. Yet the official charged with the task—a member of the Islamist an-Nahda party, which had won forty-one percent of the seats in the Assembly—somehow forgot to mention the thirty-five people who were killed in Kasserine, one of the first sites of violent state-led crackdowns. That afternoon, protests broke-out in Kasserine and neighboring towns against widespread sentiments of neglect on part of interim and later newly elected political elites in Tunis.

These sentiments of neglect were fueled by an economic reality, in which little has been achieved to ameliorate high unemployment and general economic ills plaguing the region for decades. In towns across central and Southern Tunisia, like Kasserine and Le Kef, many of those who participated in the revolution and witnessed the deaths and injuries of friends and family express frustration that little, if anything, has changed since the fall of Ben Ali. Unemployment continues to soar with virtually no job prospects on the horizon, while politics are once again centralized in the capital of Tunis to the neglect of the very towns that initially sparked the revolution.

[An exhibit at Le Kef cultural center.]

Bon Anniversaire?

On the night before the anniversary, were Le Kef citizens celebrating? In a smoky hotel bar, not far from the town’s center, some two-dozen young male Kef residents were all staring down at their glowing cell phones, texting with their friends in town about fights that had broken out, where several piles of tires had been set on fire. The town’s taxis had just called a strike and the bar’s manager—concerned that his clientele might skip on their tabs to join their friends in town—politely asked them to pay and leave. The owner arrived and helped the manager cash out and close the bar for the evening, while a Tunisian General Labor Union (UGTT) member who appeared to be in his sixties lingered over his beer and reflected on the year’s events.

The UGTT has historically been a semi-autonomous political actor, though it became increasingly coopted under the Ben Ali regime. On 14 January 2011, however, the UGTT called for a general strike just a day before the departure of Ben Ali. Yet, when offered congratulations on this eve of the revolution’s anniversary, the lone UGTT member in Le Kef showed reluctance to make any celebratory statements.

“To these people,” he said, “this is not a revolution. In fact, they [the kids in the streets at that moment] are trying to stage a new one. But nothing has changed. Even though we are pacifist and quiet as Tunisians, living in this little mountain town, we experienced one of the most violent moments of the revolution. People are upset. So many were killed, and the new interim government has promised us so much, but we still don’t have jobs.” And he said that the union—even though it cares about workers—simply was not capable of bringing about real change because of lingering internal corruption, while the people weren’t really able to pick up and start new lives in Tunis. Smiling at the owner and manager, neither of whom was a member of the union, the UGTT member asked if his comrades agreed. "Solidarity," he concluded, "is not formed through unions but only exists among friends who always watch out for each other."

[A USAID event in Le Kef.]

One hour later, the streets were rather quiet save a few burning tires. Small groups of police stood outside the Monoprix and Magazin General supermarkets, which had been looted and burned during the revolution. A group of men also stood outside of the local an-Nahda party office, protecting it from attacks. One man reported that these were not party members, but that the party paid fifty euros a night to protect the office—welcome income for the unemployed.

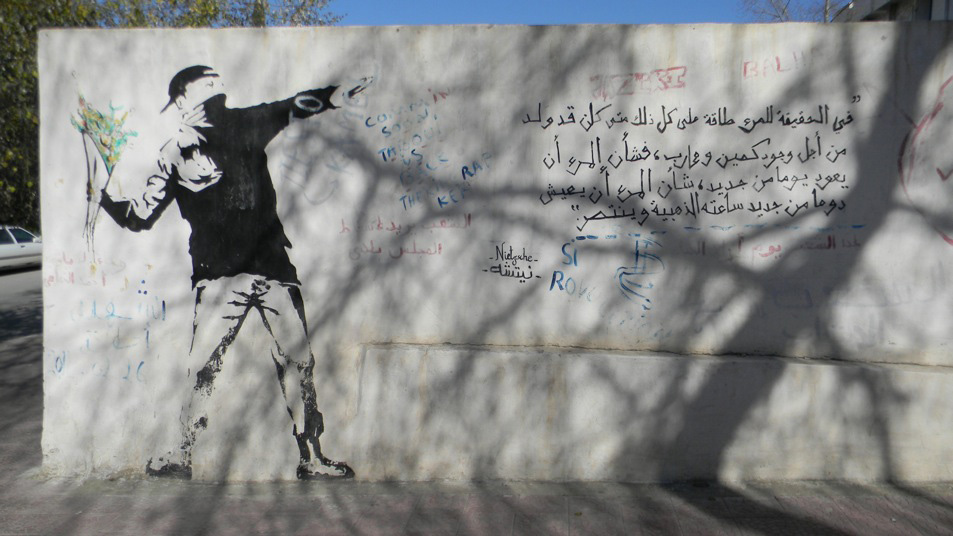

[Graffiti on a wall in Le Kef.]

The next morning, a female receptionist at a small hotel smiled nervously and refused to comment on the previous night’s events, while a police officer characterized the crowds as just a few groups of kids pulling pranks and looking to burn off steam. Two dudes at a self-consciously hip clothing store said that they had been part of the events the previous evening, and that they were actually protesting the controversial presence of the Qatari Emir in Tunisia, especially given that an-Nahda leader Rachid Ghannouchi had traveled to Qatar in recent months to ask the Emir to send aid to Tunisia. Anger over the Qatari visit and the continued neglect of the northwestern border region continued to inspire protests in Le Kef to this day.

[Graffiti in Le Kef.]

Celebrations

On the anniversary itself, several political party offices in Le Kef organized commemorative events. Music blared from speakers in theiry offices, as lectures and discussions were scheduled throughout the day. An-Nahda’s event was aimed at youth, and the audience included young men and women, the latter both with and without head scarves. Local an-Nahda officials—natives of Le Kef—acknowledged their concerns about attacks on their offices but attributed potential threats to the existence of ex-Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD) militants who they claim have continued to operate in the area since the immediate days and weeks after the revolution. The RCD was Ben Ali’s ruling party, and high-ranking party officials have been pushed from office following the revolution and excluded from official politics.

One an-Nahda official explained that the revolution and its aftermath were particularly peculiar in Le Kef. Unforeseen numbers of RCD militants flooded the small town to loot and burn virtually every shop and boutique in town. To this day, few residents know how many ex-militants continue to operate in town and whether they are quietly organizing raids. The planned attacks on the supermarkets and an-Nahda’s office, the party members stated, were actually the result of a newly and loosely formed alliance between extreme leftists (including members of the Tunisian Workers’ Communist Party or POCT) and ex-RCD militants.

Like an-Nahda, the POCT was never legalized under Ben Ali and thus never participated in elections. The goal of this overarching anarchist alliance is supposedly to weaken state institution, as RCD-ists are seeking a return to the ancient regime and many extreme leftists have refused to participate in formal post-revolutionary politics, especially elections. Although such alliances could not be confirmed, it was clear that an-Nahda, which had won a majority in Le Kef, now felt itself to be the target of post-revolutionary dissent. In a car ride to the local UGTT branch, one an-Nahda staff member gently confessed that he spent sixteen years in prison in Tunis, eleven of which were in solitary confinement. He was arrested for supporting an-Nahda in the early Ben Ali years and in 1991 received a twenty-five-year prison sentence. When he was released in 2008, he returned to his native Le Kef to build a new life. A year ago he finally married, but he expressed that his fear of a return to dictatorship and the uncertainty of events such as those the night before in Le Kef overshadow his personal happiness and his trust in post-revolutionary politics.

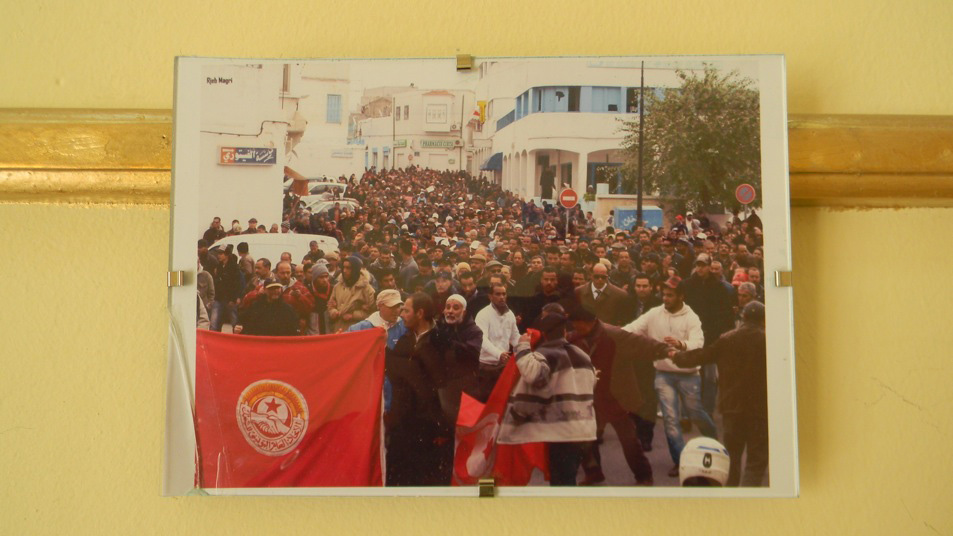

[An exhibit at the cultural center.]

Elsewhere in the town, a number of events marked the anniversary. At the Cultural Center, a photo exhibit of revolutionary moments and loud music ran non-stop, with various lectures and performances scheduled for throughout the day, including the successful one-man show “Monologue Essebsi”: a dark and comical political critique. Large banners promoting the "L’Art de L’Expression" festival, funded by USAID, cluttered the town with three planned events from 13 January to 15 January 2012.

Yet, the public event on the day of the anniversary flopped, although some dozen young residents of Le Kef did show up and spray-paint posters while a foursome improvised music. The event’s organizers claimed that the event was actually a private affair (despite the highly visible banners hung all over the town) and thus not open to the public. Observers were told that they could not take photos to talk to anyone. They were then aggressively asked to leave by the self-described (and clearly frazzled) organizer, who mentioned only security when he struggled to justify how the highly advertised public event had now became closed to the public. Overall, then, the general mood in Le Kef was subdued on the anniversary, reflecting the ambiguities expressed by the bar manager, hotel owner, UGTT member, and an-Nahda officials. Le Kef residents stood in clusters on corners and in cafes talking and looking around curiously, sometimes gathers around the political party offices blaring music, but little else seemed to be happening.

[A party office in Le Kef.]

Although being central to the early spread of the revolution, towns such as Le Kef seem to have been virtually forgotten both domestically and internationally. By comparison, the town of Sidi Bouzid with a population just shy of 40,000, now appears on Tunisian tourist maps in same sized bold letters as the capital city of Tunis (which has a greater metropolitan population of two and a half million).

Yet it remains in such small pockets as Kasserine and Le Kef that the disappointing effects of the revolution are only beginning to play out. As one an-Nahda official in Le Kef put it bluntly, "Tunisia is just entering the second stage of its Bolshevik revolution. The regime has fallen, but the contest for what comes next is only beginning to unfold." And that road is likely to be long and full of disappointments.